When it comes to recreating a certain space-time continuum on reel, there has hardly been anyone as gifted as the uniquely crafty Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray. In one way, his self-declared cinematic masterpiece ‘Charulata’ (1964), known globally as ‘The Lonely Wife’, perfectly embodies the transitioning Bengal towards the later part of the nineteenth century. This is notwithstanding the fact that the dominant critical discourse has more often than not delineated it as a romantic fable involving a married woman and her brother-in-law. The film, based on a semi-autobiographical 1901-novella by the literary genius Rabindranath Tagore, could very well be described as a feminist statement, something that was rather rare in the Indian context at that time. The movie is beset with countless elements and allusions that could make anyone sit up and take notice. Not only was the film a distinct aberration in the Indian movie-making circuit, its language was decidedly universal.

Although critics have often panned the movie for being overtly sentimental, the reality remains that it goes much beyond the portrayed emotional tale. In fact, a careful relook at the film helps us appreciate that it poignantly chronicles an invisible yet powerful conflict between love and respect, between the heart and the mind. While the luminously beautiful Charulata is evidently attracted to her mildly roguish yet talented brother-in-law Amal, the admiration and respect for her seemingly intellectual husband Bhupati stops her from unequivocally professing her love.

Charulata has been dumped to a lonely and unproductive life by her neo-liberal husband, who publishes a ‘serious’ political newspaper. The movie chronicles the upper class Bengali lifestyle of the time and in ways more than one mocks it. The introductory scene where Charulata is shown to wander about aimlessly in her queenly mansion and pointlessly peep out of the window could be considered to be a metaphor for the often futile privileges enjoyed by the then wealthy section of the society. Although Bhupati loves and cares for his wife, he doesn’t have either the time or the inclination to give her the company she needs. This is where his younger cousin Amal comes in. During Amal’s brief visit to Bhupati’s place, Bhupati asks him to stay permanently and douse Charulata’s literary curiosities. While Amal does so with pleasure, a tinge of rivalry raises its ominous head when Charulata publishes a short story without taking him into confidence.

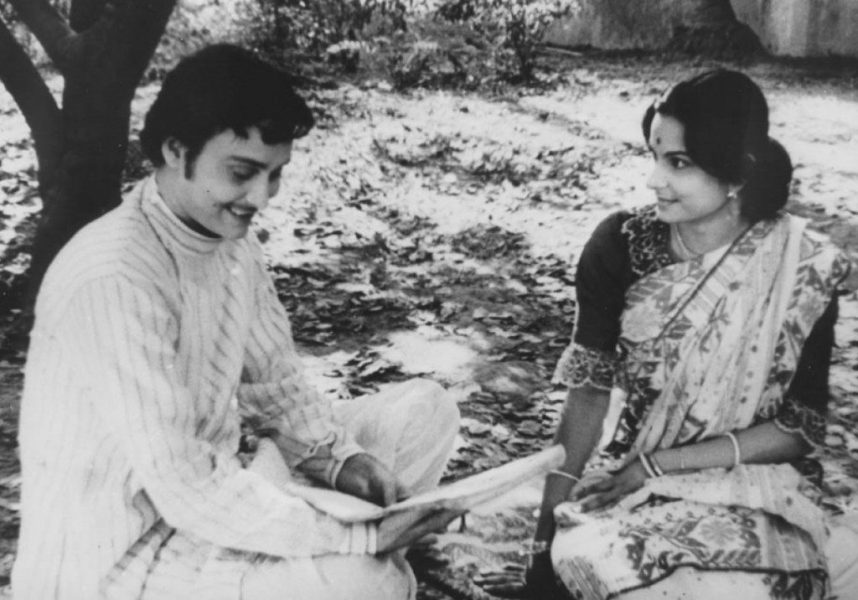

One of the most celebrated scenes from the movie shows Charulata looking at Amal while swinging in the garden and humming a Tagore song. With hardly any dialogue, Ray aesthetically establishes the romantic undertone that permeates the relationship between Charulata and Amal. The scene is characterized by an outstanding narrative style and an immaculate piece of cinematography by Subrata Mitra.

Although Charulata almost goes the distance to communicate her feelings towards Amal, he refuses to reciprocate the same subject to his deep-seated respect for Bhupati. Meanwhile, when Bhupati is rendered bankrupt, Amal, bitten by deep guilt and remorse, leaves without informing anyone. When Bhupati accidentally breaks into Charulata’s hysteric reactions at Amal’s departure, their nuptial relationship is practically taken to a point of no return, essentially establishing the central theme of ‘Nastanirh’, the Tagore classic that inspired the movie.

While viewers remain engrossed with the story and the depiction, the movie is studded with multiple cinematic layers. On one hand, the film represents the emancipation of the ignored Indian woman and her elevation from a mere bystander to an active familial participant. On the other hand, it also signifies the eternal battle between traditionalism and moral liberation. It needs to be remembered that Charulata is unambiguously more talented and capable than both the men in her life. In fact, it might not be an exaggeration to note that one of the reasons behind Amal’s intentional exit is his failed rendezvous to establish dominance over the suave Charulata, someone who gets the better of him in all senses of the term. Additionally, Charulata shows her obvious contempt for Bhupati’s work, something that pathetically fails to make any headway into the world of serious journalism.

Let this be clearly understood that ‘Charulata’ doesn’t stand in seclusion. It comprehensively points to the cultural, social and literary spectrum that was slowly but gradually evolving in the late eighteenth-century Bengal. It might be helpful to appreciate that the Western way of life was slowly assuming control over the Bengali intelligentsia of the time. Consequently, ‘Charulata’ could be considered to be a stark rejoinder to that change. Ray has repeatedly labelled ‘Charulata’ as his best creation. Subject to its thematic richness and subtle emotional undercurrents, many contemporary critics rank it above Ray’s most acclaimed creation ‘Pather Panchali’ (1955) or ‘Song of the Little Road’, as it is known to the English-speaking world.

Any discourse on ‘Charulata’ remains incomplete without a discussion on the elaborate sets that were used for making the film. Ray worked in close collaboration with the movie’s Art Director and his old associate Bansi Chandragupta to recreate the time. Ray conducted a thorough research into the Bengali society of the late eighteenth-century in order to make the film a seminal one. In fact, the production of the movie took a much longer time compared to some of his earlier cinematic ventures. All the sets were meticulously created and none of the shots were taken on actual locations.

The movie also garnered universal acclaim subject to its methodical acting. Madhabi Mukherjee, playing the role of Charulata, is at her vulnerable best. It would be justice done if it were to be said that the actress successfully blends herself with the character thereby imparting extreme realism to the film’s diegesis. Ray’s golden find Soumitra Chatterjee plays the role of Amal with an élan that is hard to match. The genteel and sophisticated Shailen Mukherjee acts out the role of Bhupati and with extreme ease.

Ray was hugely influenced by both French New Wave and Italian Neorealism. The film has distinct elements from both the global cinematic movements. In retrospect, ‘Charulata’ seems more like a reel poem, something that has been able to transcend time and space despite its obvious period characters. Indian cinema would always be indebted to ‘Charulata’ not just for having developed an alternative audio-visual discourse but also for going beyond the confines of debilitative populism.