The number of legendary names that assembled to make 1966 one of (if not the) finest years in cinematic history is astounding. Following films are backed by prolific masters of their own unique crafts, many of them working at the very top of their game to deliver works of stunning importance that all happened to converge on the very same year. A blissful piece of cinematic serendipity, very few years can boast an equally impressive line-up. Again, here’s the list of best movies of 2016.

15. Blow-Up

Michelangelo Antonioni’s flick is, in more ways than one, in fashion. It’s a story of artificiality and the aesthetic that doesn’t remotely reach the dizzying height of Michael Powel’s 1960 Peeping Tom, from which it is clearly taking a lot of its inspiration. The movie marks an important watershed in the artist’s career in terms of working outside of Italy — Blow-Up being a revered classic of British cinema despite the maestro behind it — and understandably given the rich, multi-textured mystery that lurks in its core. There is always something dark and ominous in the shadows of Antonioni’s bright pop world; and this admirable mastery of layered mood is perhaps the only thing that saves it from mediocrity.

Read More: Best Movies of 1986

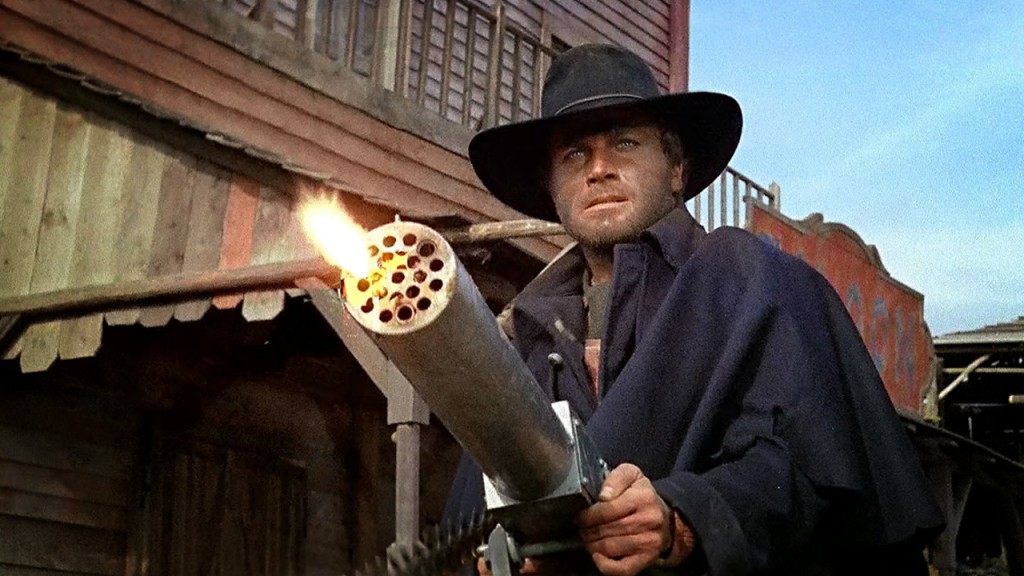

14. Django

Whilst not Spaghetti Western titan Sergio Corbucci (the other other famous Sergio)’s magnum opus, Django provides an adept primer for what the core genre has to offer outside of Leone. It’s rougher, leaner and raw in depiction of violence and interpersonal relationships. The lack of subtlety and often directorial skill does not throttle Corbucci’s ambition however, jamming his work with gems of fore-thought that speak to his passion. Such passion breathes beautifully in the climactic gundown that closes Django and is, again, a fascinating representation for the roaring lion of the Spaghetti Western slashing at the folkloric American vision of the Frontier.

Read More: Best Movies of 1987

13. Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolf?

Mike Nichols’ fabulous debut, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolf?’s fantastic screenplay as penned by Ernest Lehman Attracted colossal stars Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton- whom similar to John Travolta with Pulp Fiction were re-founding their reputations after the disaster of 1963’s Cleopatra. The former gives a career-best performance as wife Martha, quarrelling constantly with Burton’s husband George in a toxic exchange of barbs and verbal bruises that culminates in as fine a confrontation as was written in the 1960s. It’s an immaculate story and piece of acting, touched with a slight cinematic edge that the director of Fences certainly could have learned from.

Read More: Best Movies of 1988

12. Seconds

Perhaps John Frankenheimer’s greatest achievement, if also one of shamefully wasted potential, Seconds strikes out away from American cinema of the time to deliver something striking, original and perplexing in its horrors. Praised primarily for James Wong Howe’s impressive cinematography, Seconds asserts from the very first scene its ability to subvert Hollywood convention with explorative snorricam shots that distort our perception and lace the piece with an undertone of almost cosmic doom. Indeed the first third of the movie is impeccably photographed and invigorates the tone of the piece beautifully. There is a warped horror living in Seconds whose potential is undoubtedly suppressed- but Frankenheimer still manages to give us glimpses of a masterful sci-fi infused slip into the abyss during its finest moments.

Read More: Best Movies of 1989

11. The Sword of Doom

Another Japanese pulp slash bursting with cathartic action, the Sword of Doom sees two titanic Japanese actors Toshiro Mifune (Seven Samurai) and Tatsuya Nakadai (Harakiri) square off in a movie clearly inspired by the wave of Italian Westerns sweeping the world market. It’s a less complex, better choreographed Yojimbo with electrifying action scenes that see legions of samurai extras cut down in spectacular fashion- culminating in a marathon battle stacked full of stark imagery and intense exchanges of attack. In the end, the story of the Sword of Doom is lack-lustre compared to its ferocious and authoritatively composed fight scenes, though it is evidence enough for the skill of director Kihachi Okamoto that he can hold the movie for 2 hours on little more than a thread-bare tale and the strength of his visual style. A shame that the proposed sequels were never made.

Read More: Best Movies of 1990

10. The War is Over

Alain Resnais killed it in this decade, from Last Year at Marienbad to Muriel, the War is Over and Je T’aime Je T’aime he displayed a remarkable willingness to experiment with film form that rose far above the cinematic virtue so lauded by contemporaries of the French New Wave like Goddard and Truffaut. Very little in cinema moves quite like a Resnais film and this is no exception, blending poetic editing and photography with a melancholic stream of memory that remembers the horrors of war and draws fantastic performances out of its leads, most notably Yves Montand (Le Cercle Rouge). The man never struck out with a cold hard miss and fittingly enough this place as a suitable transition from imperfect births of experimentation like Blow-Up and Seconds to far more successful ventures in bending the cinematic language.

Read More: Best Movies of 1991

9. Tokyo Drifter

The recently departed Seijun Suzuki is another fascinating piece of cinematic history, clashing constantly with his studio over the increasingly subversive and ‘artistic’ departures his movies would make from the mainstream Japanese crime flicks they commissioned him for. It was Tokyo Drifter’s glorious colour photography riding the pop-art rainbow of the 1960s was what led them to cut his budgets for following works to stifle this unwanted creativity (1967’s Branded to Kill then ironically becoming his crowning achievement), and Suzuki’s seductively forbidden aesthetic gives way to a satisfying story of cops and criminals which pulses with the blast of the crimson-hued gunfire that rages across its narrative. It’s awash with ravishing battles and interesting characters that make this a far more worthy cultural icon than Blow-Up and a movie that has thankfully, deservedly grown in stature after initial throttling by a Japan in no way ready for what it had to offer.

Read More: Best Movies of 1992

8. Second Breath

Jean-Pierre Melville’s thrilling warm-up for Le Cercle Rouge’s own heist caper, Second Breath is as carefully controlled and stylistically effective as any of his best works, ranking alongside them with its own brand of Melvillian crimeworld odyssey that picks up in a prison escape and continues to host character and situations that compliment his method throughout the runtime. Melville always made a similar sort of movie- but it is the abundantly clear evolution between these films that makes that same-old crime story worth watching again and again. His development of what would become pitch-perfect directorial style in ‘67’s Le Samourai is a testament to the artist’s humility and ability to learn- which is crucial to the success of any great director. Second Breath is the final lesson in a career of rising anticipation and more than worth a watch for it.

Read More: Best Movies of 1993

7. Au Hasard Balthazar

Robert Bresson’s illuminating study on our nature through the eyes of a domesticated animal is an oft unpleasant look at the malice that sits behind the heart of humanity. It exposes and explores more about us than many movies made specifically examining the drama between human beings- prising open dark secrets of carnality and cruelty with a light touch which pursues absolute honesty in favour of a romantic vision of the heroes and villains that cloud much media. Each character is imperfect, impure and tainted by some desire for dominance in a grim, austere country world- leading to a uniquely intelligent and warm observation of relationships in all their forms.

Read More: Best Movies of 1994

6. The Face of Another

Hiroshi Teshigahara always found fantastic stories that suited his cinematic technique perfectly, and perhaps the most beautifully marriage of director and script comes with the Face of Another. A limitlessly eerie, glacial study of human alienation and transference of identity- it showcases the oddly captivating coldness that Teshigahara mastered in his previous work, the masterful Woman in the Dunes, and ends with just about as hopelessly unsettling a scene as you could imagine. It’s interesting to consider and contrast the efforts of three directors on this list, Frankenheimer, Teshigahara and later Bergman with Persona– and how they approached abstracted identity in a different way, each less physical than the last. An insight into the differences between American, European and Asian storytelling, for sure- and three fantastic films to boot.

Read More: Best Movies of 1995

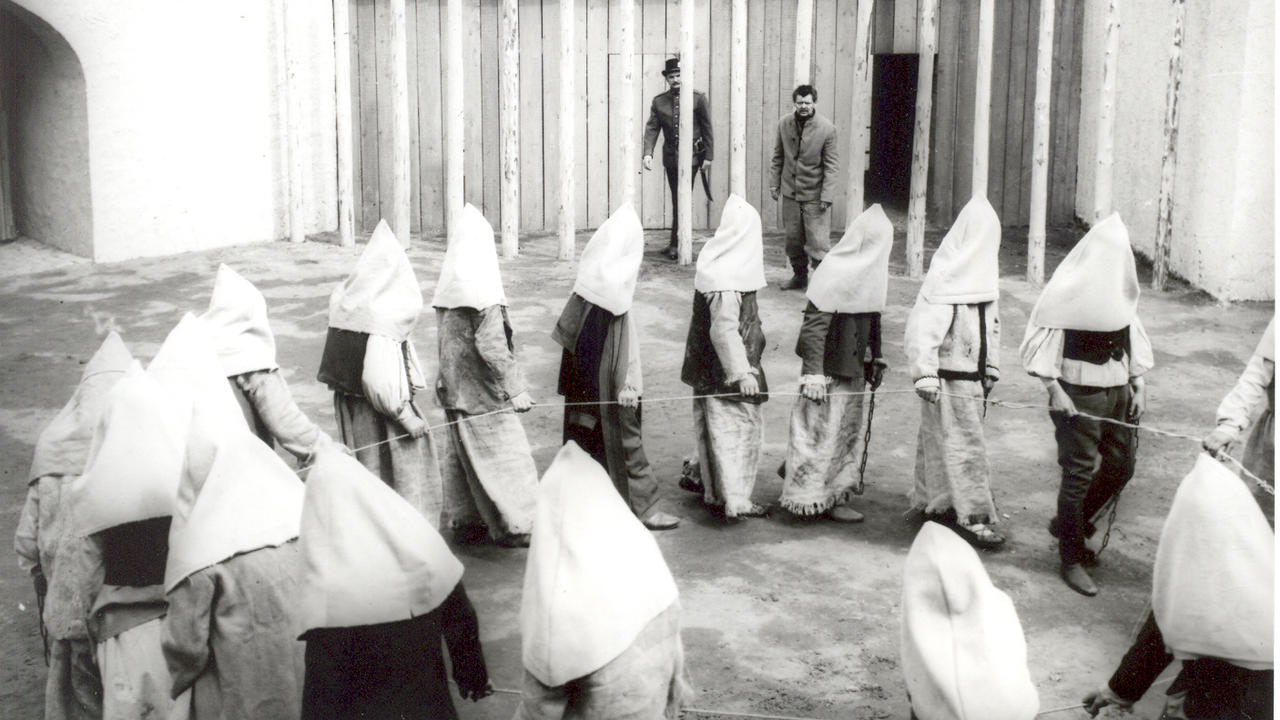

5. The Round-Up

The criminally underseen Miklós Jancsó’s only real ‘famous’ film, The Round-Up tells the tale of a Hungarian prison camp and its routine practice of psychological torture upon a swelling sea of weary occupants. Barren lives devoid of joy and pockmarked by pain are the core that holds this nightmarish carnival together, strung along by cruel set-pieces and genuine, believable human suffering on the deepest level that marks it out as a frighteningly documentarian piece of film-making. One could easily believe in its abject observation that what we are seeing is a reality- evidence to its utterly masterful realisation.

Read More: Best Movies of 1996

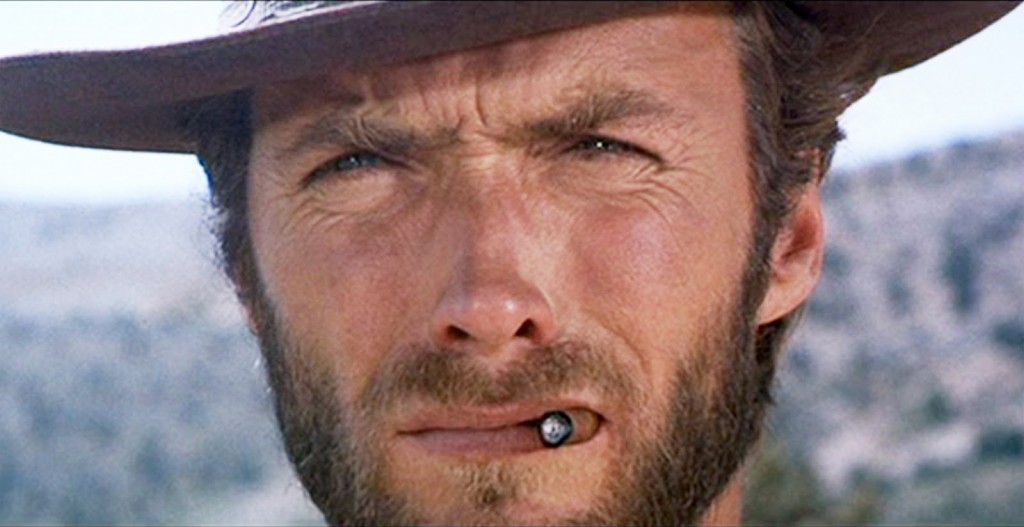

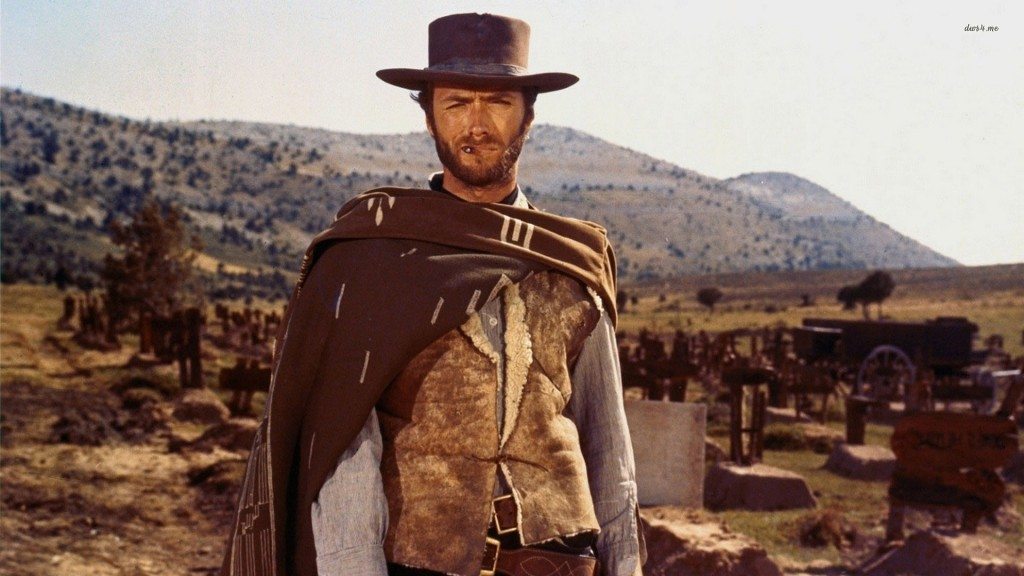

4. The Good, the Bad & the Ugly

In short, the Good, the Bad & the Ugly is the kind of film cinema was made for. It’s a work of bracing viscerally- pumping to Ennio Morricone’s immortal soundtrack and dazzling audiences with spectacular displays of both scale and skill on director Sergio Leone’s part. A grand epic with intimate stakes and scene after gorgeously realized scene of classic moments- there are few westerns to match it. Its timid strains towards a more profound look at the nature of violence is eclipsed and fundamentally undermined by the flash of its own bloodshed- but Leone’s cast-iron vision far outweighs the imbalance of such an otherwise compelling adventure.

Read More: Best Movies of 1997

3. Persona

Another movie that fully explores the potential of the medium, Persona plays through a series of uninterrupted conversations that weave in and out with complex psychological reveals and hidden fears- masterfully recited to a silent witness who plies all of this out of her victim without a word. The writing is allowed to shine through two exceptional performances by Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullman, complimented again by liquid-fast editing, married to some of the finest cinematography we have by Sven Nykvist and finally iced with by far Bergman’s most inspired directorial work. There’s very little else to say: Persona is simply electric.

Read More: Best Movies of 1998

2. The Battle of Algiers

From electric to volcanic, The Battle of Algiers marks yet another crucial landmark in film-making with a masterful retelling of the Algerian war for independence that raged throughout the 1950s, banned in France for several years due to its inflammatory nature. Despite this, however, Italian director Gillo Pontecorvo’s vision is exceptionally neutral- highlighting the humanity (at both its ugliest and most impassioned) on both sides of the barbed wire. It packs innovative editing, affecting realism and most importantly a profound reflection on the international mentality that penetrated every single person present at the time- incendiary riots charged with a palpable fervour for freedom. Critical cinema.

Read More: Best Movies of 1972

1. Andrei Rublev

As a cherry on top of all of this wonderful cinema, Andrei Rublev definitively stands as the Greatest Film I have ever seen. I doubt anything else needs to be said: Once you’ve worked your way through the preceding 14 flicks- Tarkovsky’s monumental magnum opus is an irrefutable must.

Read More: Best Movies of 1973