Going straight into the history books as the most abhorrent gaffe in the history of the Oscars (including the “Come on up here, Frank!” fiasco from the 1933 ceremony), the initial announcement of ‘La La Land’ as the Best Picture winner and subsequently loser to an equally worthy artistic undertaking ‘Moonlight’ was instantly surprising and somewhat gratifying to me. A film like ‘La La Land’ which has been the target of such incessant backlash ever since it started sweeping all sorts of awards, citing reasons that were absurdly blaming random character choices and political relevance in a film that could not be more apolitical if it tried, would have suffered so much more of this antipathy had it been the actual winner. And thus, I was immensely satisfied with the result. Because a fantastic film made on $1.5 million had now the opportunity to become a serious box-office success like ‘Spotlight’ last year and ‘La La Land’ which has already grossed over $369 million dollars worldwide, could be treated much more kindly in the years to come.

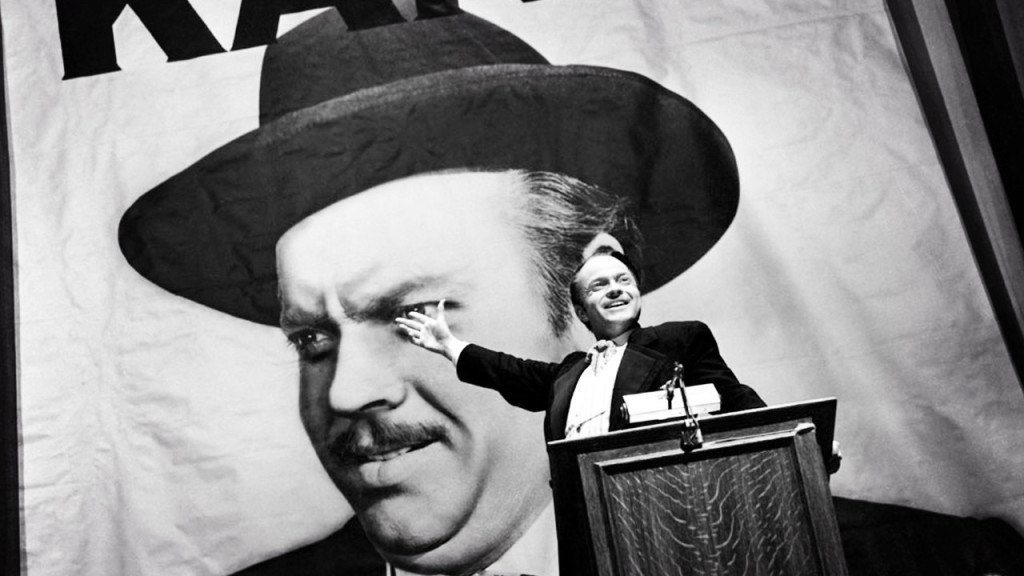

I read a Collider article the other day that said ‘How Green Was My Valley’, the film that is now mostly remembered in the public consciousness for taking down Orson Welles’s ‘Citizen Kane’ for the Best Picture award, was the second greatest Best Picture winner of all time, ahead of both ‘The Godfather’ films. It was an absurd categorization that I had never seen anyone make before, having spent countless hours reading stuff like this on the internet, and it prompted me to the realization that films that won the Best Picture Oscar years before we actually we consume them, are always assessed by us with that crown on their head. It clouds our judgement of them and is very difficult to shake away, especially if they beat a highly worthy film that then benefits from the position of being the “underrated” one. Riddle me this, can anyone now call ‘Citizen Kane’ underrated? That is one of the ramifications of losing a Best Picture Oscar. You’re so customarily and with such fervor called underrated, you completely cease being so.

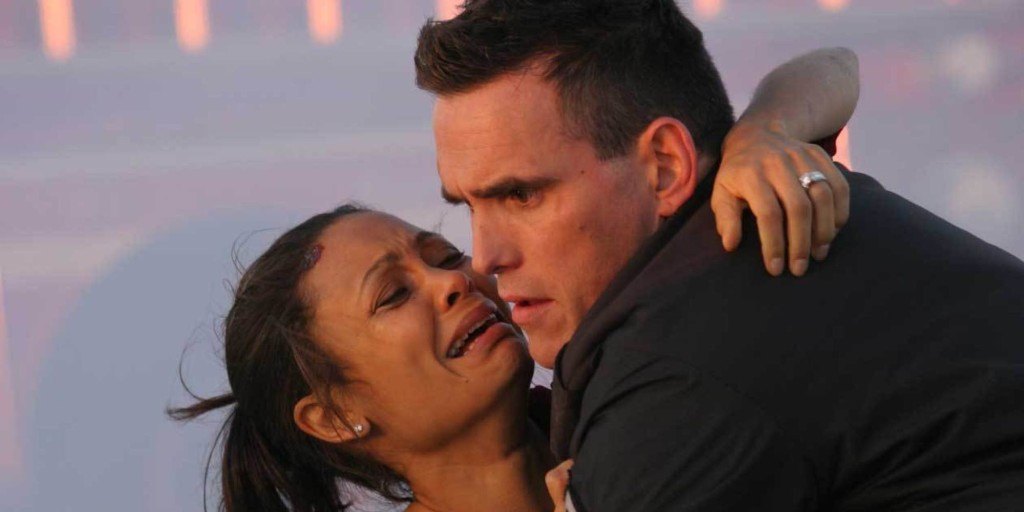

One of the most talked-about Best Picture triumphs, because it not only showcases unpredictability with the Academy Awards, but also projects two very important truths about the cultural event: first, campaigning matters (sometimes more than the individual merits of the nominees) and second, you can never beat Weinstein at it, was the victory of John Madden’s romantic comedy set in the Elizabethan era, ‘Shakespeare in Love’ over Steven Spielberg’s World War II drama, ‘Saving Private Ryan’. It made sure, that ‘Ryan’, the admittedly superior film would be an unabashed cinephile favorite, while ‘Shakespeare’, a film much less deeper in its storytelling and rendered quite frivolous due to frequent comparisons to the film epic, would be lovingly despised by all film enthusiasts, despite having, what I believe to be one of the greatest screenplays of all time.

But if we consider why such a phenomenon begins to manifest itself in film discussions, one finds that it’s the widely publicized ceremony that’s at fault here. It’s the humongous and somewhat disproportionate cultural impact of the Oscars, whose relevance has never been seriously warranted by their vastly limited perspective, that makes sure the discussion around the films they end up honoring always involves them. At times, it seems the most awarded becomes far less preferable to the one left out and is quickly stripped of its universally beloved status. Would the blemishes of ‘Titanic’ be so blatantly discussed had it not won 11 Oscars and tied the record for most wins and most nominations in history? I can’t be entirely certain but the newspaper headlines that such records make post-announcement make it difficult for people who believed there were much superior films that year to not dismiss the romantic epic as much too sappy and poorly written. With the 20 years that have passed since the film’s release, that dismissal has only grown in stature and volume, while the film’s exalted score and distinguishable cinematography are regrettably looked over.

The key to watching films, I have come to believe from my experience of being a passionate consumer of the cinematic art for sometime now, is that no embellishments matter. Whether the film was hailed as a masterpiece or repudiated as trash, it is your opinion that is the only valid one. The Academy, as is evidenced by their many miscalculations and oversights throughout film history, cannot be relied upon to be the perfect barometer. Yes, ‘Crash’ is exceedingly unworthy of being called the best film of 2005 over ‘Brokeback Mountain’. But some would vehemently disagree with me, and I cannot take what they received intellectually and emotionally from a film I found overtly preachy, away from them. But when they begin a conversation with, “I preferred ‘Crash’ to ‘Brokeback Mountain’ “, I suspect a lot of them are denied the so-called street cred in the film fanatic communities. One such conversation in a movie club I’m proud to be part of made me comprehend the intensity of our affection for the underdog and how far we’re willing to go to proclaim the rival that makes our favorite the underdog as complete muck. And our collective consciousness then leads to it becoming cemented for future generations to only see them in this light and not evaluate their virtues without any preconceptions, which in my head, is elemental to fully experiencing cinema.

I markedly recall a friend of mine stating with much verve to a huge gathering that he hadn’t seen ‘Kramer V. Kramer’ but if it won Best Picture over ‘Apocalypse Now’, it can’t possibly be any good. The statement didn’t make any sense to me then and seems even more ridiculous in hindsight. Unarguably, ‘Apocalypse Now’ is a far more engaging and miraculous cinematic experience, but you can’t invalidate the opinions of those who deeply enjoyed the intimate brilliance of ‘Kramer’, your humble author included. More importantly, in your glorious snubbing of the Best Picture winner because your choice wasn’t rewarded, you contribute to the gradual fading of other excellent nominees, in this case for instance the magnificent ‘All That Jazz’ from the whole parlay, which in my mind is unacceptable.

Thus, my final advice to you, my worthy reader, would be that no matter how many think-pieces you might stumble upon that reduce discussion about cinema to the largely unenlightened group of industry members who fashion themselves with the title ‘Academy’, never allow your experience of a film to be eclipsed by such opinions. You define the times you live in, and even if the community surrounding you has already decided what films to celebrate and which ones to lambaste, your relationship with any particular piece of art decides its longevity. So if you feel that not enough people talk about how excellent ‘Tom Jones’ or ‘An American in Paris’ or even ‘Out of Africa’ are, start the conversation. Wouldn’t Rachmaninoff and Christopher Marlowe been lost to us had no one from the generations before us, tried to preserve their genius amidst the deafening applaud Mozart and Shakespeare were afforded? It’s our turn now, and the “I-am-just-a-toddler-but-I-own-an-iPad” generation might thank us someday.