I don’t endorse the concreteness the word ‘explanation’ invites. No piece of art can be definitively assigned a singular, unambiguous, incontestable perspective. It changes, from viewer to viewer and the mood they see the film in. And because of my unshakable faith in the experientiality of cinema over its intellectual or political or logical ambitions, any explanation that would profess to define the confines of the experience a film can engender is hard for me to find creditable. For me, even the chair I’m sitting in, the colors of walls surrounding me, the way the light hits the screen can become parts of that experience. Because our opinion of any cinematic work transpires from our memory of consuming it and it’s positively preposterous for anyone to claim to have knowledge of mine or anyone else’s memories.

That said, knowledge regarding film doesn’t end with your experience. The opinions you hear continue to etch in your head some image of the film and that continues to evolve as you come across more and more of them. And that is never necessarily a bad thing. Intellectual discussion on cinema is stimulating, informative and lends your perspective the potential of being virtually limitless, rather than pinning it down to one obscure, final “solution”. Therefore, my intention with the following article is not to cement in any way your expectations of this unadulterated masterpiece, but to merely extol its many complexities and its warranted place at the top of the filmography of an artist who is quite possibly the single greatest filmmaker alive.

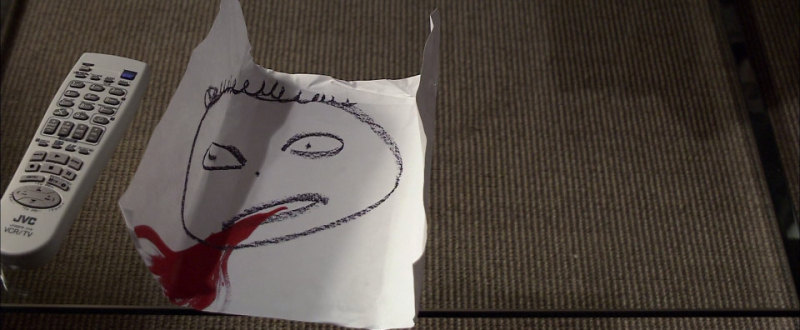

‘Caché’s’ plot doesn’t demand as piercing a look as the stature of the auteur behind it might suggest. Georges and Anne Laurent (names given to almost all of the central couples in his films) have lived in a bourgeois house in Paris for almost all of their mundane lives characterized by the increasingly contemporary sensibility of going to work, coming back home and repeating the whole thing come next morning. A video tape wrapped in a polythene bag arrives at their doorstep followed by many others just as disturbing, accompanied by horrifying, childish drawings. It throws a wrench in their seemingly peaceful existence and in trademark Haneke stillness, paints one hauntingly agonizing image after the other.

So I offer to you only the pieces to the puzzle (if I may call it so) and you might take them and make your own whole, because even the pieces would fit differently for each one of you. Or you could just call this my share of the collective knowledge of the film, that might or might not add to your own and help in a more meaningful and hopefully even more layered general understanding of this unnerving stroke of genius.

SPOILERS AHEAD.

Blood Memories

All through Haneke’s bleak cinematic trajectory there is a strong sense of grounded, brutal yet poetic violence that lingers in the consciousness of viewer and is guaranteed to haunt someone like me whose repugnance to violence borders on hostility. ‘The Piano Teacher’ had that tragic, bleak moment where splashes of Erika’s blood dirty her night dress, and I could neither look, nor look away. In this one, blood is at the forefront. Not only in memories of a beheaded rooster flapping on the ground (mirroring Haneke’s own childhood memory, leading him to share my aversion to violence), but in visions our protagonist Georges has of Majid from his childhood and those horrific crayon sketches as well. Georges’s blood memories are ironically colored with blood red and become such inseparable parts of his being that they begin to engulf everything around him.

The Dynamics of a Relationship

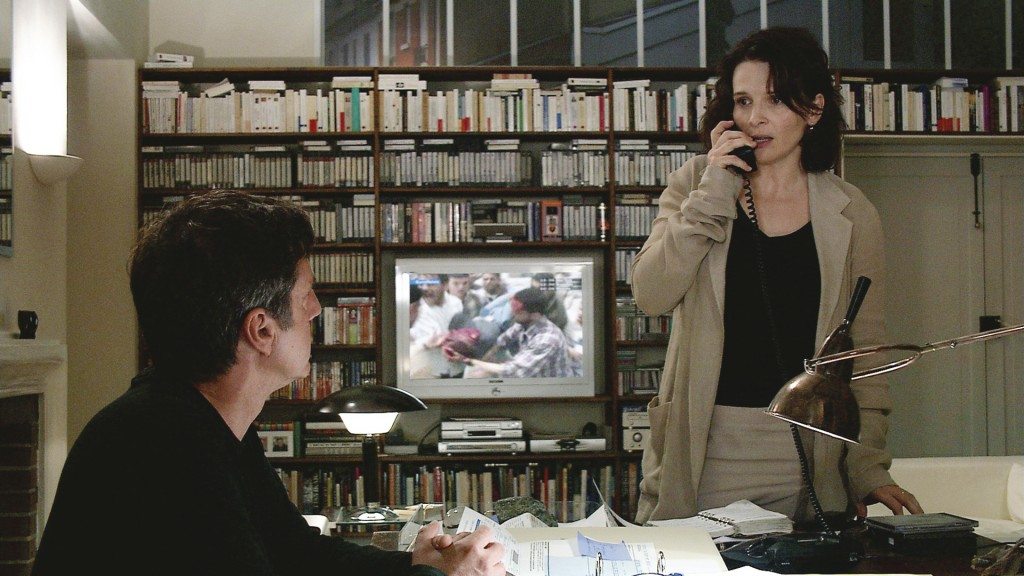

To what degree can we be in control of our prerogative in a relationship? Do we hold any power over the other person, our image in his/her head, or even what instruments bring us to their minds? Anne, played by a steely, vulnerable Juliette Binoche, wonders the same. And so do the rest of characters: Pierrot, their 12-year-old son whose perplexing contribution to the narrative seems accidental or worse, sentimental at first, but acts as another layer to the thematic premeditation of the filmmaker. Everyone surrounding Georges is vying to hold significance in his cognizance. They extend hands to establish faith, and while Pierrot seems to have given up and Anne is caught by surprise when she finds it inexplicably absent, Majid’s is just as dubious to us as it is to Georges, but could possibly be the most welcoming.

The Truculent Isolation

Most of all great art is intended to make us feel less alone. And thus so much of all great art finds its kernel in the cruelty of loneliness. Majid had been alienated from Georges’s rich family and the privileges that would’ve come with his adoption by Georges’s parents, because Georges began to feel secluded and helped in Majid’s transfer to an orphanage instead. Pierrot senses an inaccessibility to his parents who seem to be so engrossed in their own professional and social intricacies, to an extent where he is led to believe his mother is cheating on his father, underscoring Anne’s remoteness to her husband plausibly existing even before the tapes arrived. And as much as Georges’s world is susceptible to dismantling, Majid has unintentionally denied his son the pain-free childhood he was never afforded. His son then carries the same burden, cutoff from the liberties of a much more insouciant world.

The Austrian Sense of Humor

In an interview for ‘Elle’ at the Toronto International Film Festival last year, Isabelle Huppert said that Haneke imbued ‘The Piano Teacher’ with an Austrian sense of humor. You’d be hard pressed to descry anything humorous in that desolate film, but yes, there are portions of authoritative irony in all Haneke films. ‘Amour’ plays with the brutality of the circle of life. ‘Funny Games’ is intended to be a rebuke to all filmmaking that believes in conjuring entertainment from something as deadly serious as violence.

‘Caché’ is the sharpest in terms of mocking its protagonist’s sense of reality and his delusion that he possesses any ability to be in control of it. In one brilliant jump cut, Haneke lays bare all of Georges’s insecurity as a cyclist wheels past him and Anne as they walk out of their house nearly hitting them. He proceeds to yell at the young man, both physically and mentally (at the time) his superior, and is easily overpowered. Weakness is spectacularly difficult to accept, but it exists in all of us and our evasion of that realization makes our approval of reality even harder.

The Unnerving Stillness

The most trademark Haneke move is to put the camera somewhere in the middle of the events unfolding and just observe life for a few minutes, lending a disturbing stillness to the narrative. Nothing happens and we are not imparted the opportunity to be off the edge of our seats for a second because years of viewing fluidly transient cinema has made us accustomed to swift cuts and shifts in perspective.

In Haneke’s films, the perspective doesn’t belong to any one character, it belongs entirely to the filmmaker first and then the spectator, and so its shifting is not essential at all. In ‘Caché’, though, Haneke pulls off the most meta of tricks: he makes the still shots part of the story. The Laurent family are being taped, watched, observed. The film opens with a still shot that is later revealed to be from one of these tapes and ends with a similar one. But the last one involves two people who could plausibly be involved with the recording of those tapes: Majid’s son and Pierrot. And we’re left to wonder if this is our film or just one of the tapes.

Memory Manipulation

Memory is raw, unfurnished and utterly unconscious. But is it, truly? Doesn’t our experience, our situation, our age, our perspective redefine our own memories? Don’t we look at our childhood with more nostalgia today then we did yesterday? But the question here isn’t do we channel our experience through our visions of the past. The question is do we do it to an extent that we alter our memories? Georges has periodic visions of his childhood with Majid. He’s seen splitting blood and beheading roosters and terrorizing the six-year old Georges. But to what degree should they be believed to be unadulterated truth? Did Majid suffer from tuberculosis or was that a tale fabricated by Georges to get Majid thrown out? We are given ambiguous answers and a concrete ideology: our mind possesses the power to manipulate our historical reality, and more often than not, we repudiate the truth in favor of our own version of it.

The Children

‘Caché’ ends with the children of Majid and Georges talking to each other. Viewers unaccustomed to Haneke’s camera would have a hard time even discerning them from the crowd in Pierrot’s school. They are talking, but we can’t hear them. The dilemma that we have faced throughout the film visits us again, and this time we get no explanation. The movie ends and credits begin to roll. We are not given a definitive answer on whether this is a tape or the film. If this is the tape, we can count out Majid’s son and Pierrot as suspects behind those deliveries and if not, the scene pretty much establishes them as co-conspirators.

Majid and Georges have through their own misery and deluded ideas of comfort, cut their own children off and how the reflection of their misgivings manifests itself in them is left entirely to our imagination and thus is brilliantly terrifying. Take for instance how Georges and Anne consider the tapes to be a silly game played by one of Pierrot’s friends and repeatedly decide against bringing it up with Pierrot. What would that non-existent confrontation have revealed can or cannot be easily guessed, but it does drive in the point of how reality is full of missed opportunities and how our knowledge of our children and our parents is always inadequate.

The Smoking Gun

Roger Ebert in his review of ‘Caché’ pointed to a “smoking gun” at the nearly 20-minute mark. He then used another article to discuss that scene which sees Georges dreaming of a blood spewing Majid. He then proceeds to speculate that maybe this is a sign of Georges’s innocence and some evidence, albeit highly abstract, that Majid did have some health problems. He also dismisses Majid as a conspirator in those tapes and almost all among us do the same when we see Majid for the first time. Maurice Bénichou’s incredible performance is there solely to cement Majid’s honesty. But even Ebert is reluctant in labeling the “smoking gun” concrete and I happen to agree with him.

If I were to tell you that the explanation that Pierrot and Majid’s son conspired to send the tapes to Georges and Anne and Majid did have tuberculosis and more importantly, if you took me for my word, would you ever lend a thought to the mystery of ‘Caché’? So I’ll take my cue from Ebert and say that there is a smoking gun, and it’s at the 1-hour-49-minute mark. But who it exonerates and who it convicts is up to you.

The Slumber

Stanley Kubrick ended his spellbinding career with a glorious statement on the blissful, placid sleep that is the modern life. With all our wants increasingly attainable and our sense of comfort rarely challenged, we gradually, without any awareness of it, doze off, until, something wakes us up. In the brilliant ‘Eyes Wide Shut’, it’s done through an act of cruelty or kindness, whichever way you see it, by Nicole Kidman‘s character Alice. Here, the tapes slap Georges and his world back to reality. They represent the fear of being so intimately observed by someone totally unknown or worse, someone known far too well.

Georges and his relationships begin to unravel, revealing a profound, long-running ignorance in everything he has done since he was a child and because he could get away it, he never woke up. But unlike ‘Eyes Wide Shut’, where that awakening leads to a more valued living, ‘Caché’ just puts Georges back to sleep once the conflicts are over; its bleak exhibition of the contemporary middle class even closer to reality than Kubrick’s masterpiece.

The Misconception of Happiness

Michael Haneke is often accused of always dealing in bleak narratives. That characterization is completely unfair because what he essentially does is provide humane insights into the darkness that envelopes us all, how our flawed perceptions lead to agonizing isolation and how our delusions reduce our chances to overcome said isolation.

‘Caché’ is not only a massive, searing document that points to viciousness of the 1961 Seine River Massacre, and our inhumanity as a society, but also a poetically universal character study. Georges, our protagonist, perceives life and his presence as a social being in a distorted sense of joy. He runs away from the comfort of trusting and communicating with others. He relishes his alienation, just as he alienates so many who hold him so dear. With that, Haneke mocks the generation that wishes to be left alone. His camera is at times unusually distant, just as so many of us are in relation to our surroundings. But in his control, we have to confront our indecency, our inconsideration, and our reality.

Read More in Explainers: The Others | The Sixth Sense| The Usual Suspects