Superhero movies are hot property right now, and they will be for the foreseeable future as well. No living soul in the current time can deny that, and numerous superhero movies from the comic book giants DC and Marvel coming out by the dozens every year will ensure that. Not just movies, superheroes and the accompanying mania have effectively taken over our television slots, our merchandise spots, even the social media, and in the process, have established themselves as a full-fledged genre of films in themselves.

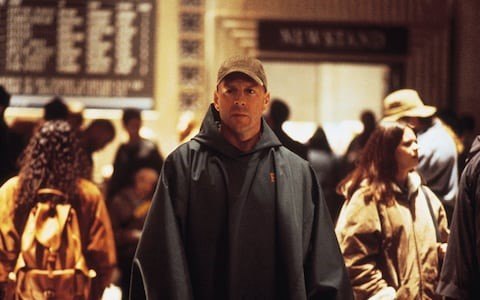

Amidst the current clutter of superhero cinema that we have, I wonder how a film like ‘Unbreakable’ would do. M. Night Shyamalan’s seminal piece of superhero fiction, ‘Unbreakable’, is a completely original product that spawned a franchise of its own, deconstructed the genre and the hype behind it, effectively exploring the very genesis of what makes a superhero. There is a reason that till date, the film is counted as a frontrunner when it comes to listing the best superhero movies ever made, even though it is unlike any other superhero movie that you may have seen. It’s a definite slow burn, takes time to set things up, but in the process, raises some important pointers about the genre and its commonalities and tropes as well, while at the same time appealing to the inherent superhero fan in you.

The way the film puts a twist on everything that you know and love about superhero films is, for the lack of a better word, unprecedented, and though this writeup is one too many years late, I sincerely hope that reading it can certainly add to the experience of it. In conjunction with that, if you have seen ‘Split’ and ‘Glass’, among the unlikeliest sequels ever made, you are in for a good read because I will be drawing parallels to these later films somewhere in the writeup. Read on.

The Ending

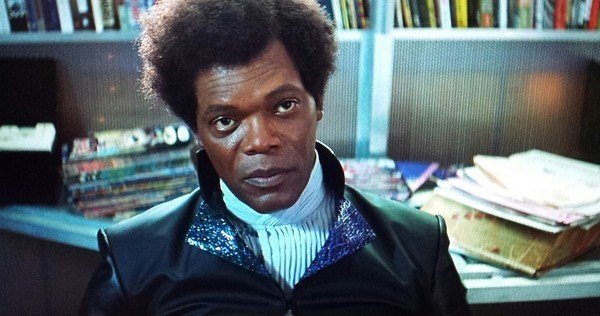

“You know what the scariest thing is? To not know your place in this world. To not know why you’re here. That’s just an awful feeling. I almost gave up hope. There were so many times I questioned myself. But I found you. So many sacrifices, just to find you.Now that we know who you are, I know who I am. I’m not a mistake! It all makes sense! In a comic, you know how you can tell who the arch-villain’s going to be? He’s the exact opposite of the hero. And most times they’re friends, like you and me! I should’ve known way back when. You know why, David? Because of the kids. They called me Mr Glass.”

In my opinion, this is quite simply one of the most iconic endings of its decade. Not the best twist ending I agree, especially when you consider something like ‘The Sixth Sense’, the other Shyamalan directorial that redefined the term twist ending for 21st century audiences, but certainly quite iconic, especially the last part, wherein Elijah Price introduces himself with his now famous moniker, Mr. Glass. The meaning of it too is quite clear. Right after discovering his powers and confessing to his son that he was right about his superpowers, he visits Limited Edition, Elijah’s comic book art gallery, wherein he indulges in a conversation with Elijah’s mother about villains, their kinds and their dichotomous relationship with the hero.

Thereafter, David confronts Elijah at the back of the store when the former urges that he shake his hand. It would be worth noting that Mr. Glass actually wishes to confess, since he is aware of David’s extrasensory abilities, and knew that his truth would be out the moment David touched him for a handshake, which would also explain his rather sinister and unperturbed reaction later upon the revelation.

The truth that David discovers is that Elijah was behind the derailment of the Philadelphia Eastrail, via which he was commuting back home from an interview in New York, killing hundreds and leaving him the only survivor. This lead to him discovering his powers and putting into motion, the sequence of events presented in the film. Not only that, the flashback that David sees and physical evidence in Elijah’s room point towards his involvement in a number of other terrorist activities, including an airport blast and a building fire, earlier expressly mentioned in the film, as part of his search for somebody on the opposite end of the physical spectrum as him, someone unbreakable, leading to the fulfillment of his comic book fantasy. He also reveals to David that finding him imbued lost purpose back into Elijah’s life, and that he was happy to associate himself as the villain to David’s hero, a complete antithesis, rejoicing that he was not a mistake as he might have been led to believe during his childhood owing to his condition.

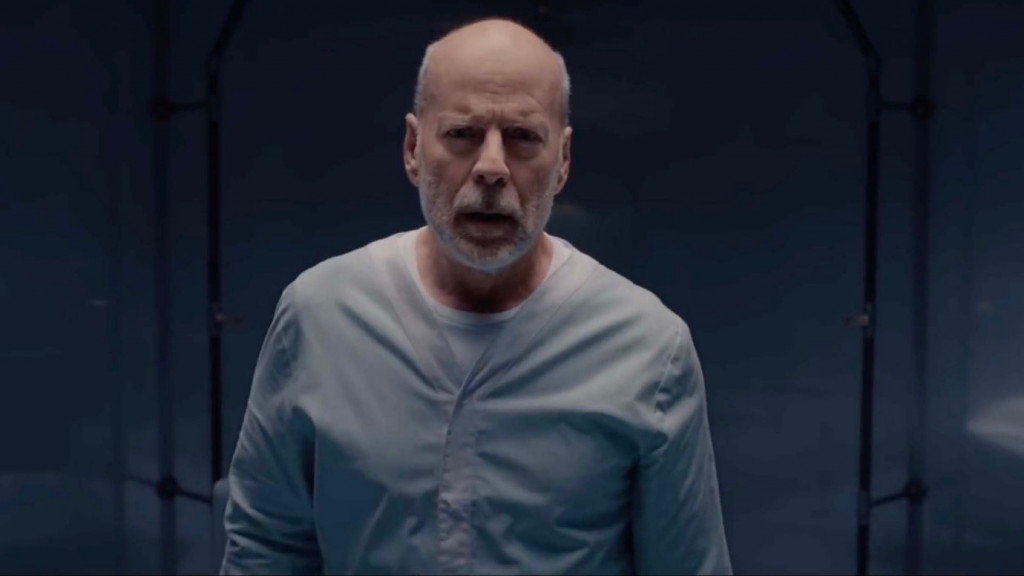

David, of course, is disgusted and horrified over Elijah’s acts and quickly departs. It is later revealed that he led authorities to his place where sufficient physical evidence for at least three acts of terrorism were uncovered, which is sufficient to place Elijah in an institution for the criminally insane, the one we see in ‘Glass (2019), where eventually David and Kevin Wendall Crumb (from Split) land up.

They Called Me Mr. Glass!

The most interesting part of this finale, apart from obviously the big reveal is the particular choice of words Elijah uses to put across why, in his opinion, all of it would seem like providence. He refers to certain kids and terms them the reason why he should have known that he was a villain all along, and that too one with a name fitting of a supervillain from the comics. While elaborating all this, it would do us all a world of good if we could remember that Elijah is, in his veins, a true blue comic book fanatic, to an extent that he feels real life should (and does on several instances) mimic comics.

With that established, what Elijah simply means is that as a complete antithesis, the perfect villain and a complete opposite to his superhero discovery David, who was quite literally unbreakable, his moniker, Mr. Glass was a rather fitting one, stemming from his condition of frailty because of which he could easily break the bones in his body. He further considers himself, as elaborated by Elijah’s mother earlier, to be the kind of supervillain who poses a mental challenge to the superhero, rather than being his physical equal.

The Genesis of a Superhero: Themes

I have been a fan of anything even remotely related to superheroes since as long as I can remember, and while ‘Unbreakable’ was nothing as I’d hoped it’d be, reading it as a part of a number of lists claiming it to be among the best ‘superhero’ films ever made, I was quite intrigued as to what this would hold in store for me. Safe to say, it is easily the most unconventional movie of its genre that I have seen, and I came out positively surprised when I finally ended up seeing it. In fact, it is hardly a superhero film at all. Although its three part narrative, typical to comic book origin story for both the villain and the hero, their relationship, the discovery of the hero’s powers and the final confrontation, which here is obviously sans the CGI mayhem that constitutes a majority of the superhero films today would state otherwise, it is, on the contrary, a whole soul Shyamalan thriller disguised as a superhero movie.

Shyamalan does what he does best when he puts his own trademark twist on familiar tropes from superhero movies: the regular life of the hero before he discovers his powers, the villain, the testing of his powers, and finally rising to the occasion and assuming his mantle, and makes them his own. Of course, here the villain himself was more brain than brawn as confessed by Elijah’s mother during the final bits of the film, and was instrumental in finding and discovering the ‘hero’ David Dunn.

Even the relationship between the ‘hero’ and the ‘villain’ borrows and works on a certain typicality, replete of course with its own take. The closest parallel that comes to mind, not in the strictest sense obviously, are the iconic DC duo Batman and his arch nemesis, the Joker. According to a few comic book arcs, one is responsible for the insurgence and emergence of the other, both are the complete antithesis of the other, the complete foil, and that both, despite being enemies, acknowledge the existence of the other in a manner that wouldn’t signify such. In short, the two complete each other, as in the Joker’s words. After they have squared off for long enough, the Joker is right in admitting, both in his comic book and film versions, that maybe they were indeed destined to do this forever, that at least he derived a sense of purpose from the other’s existence.

Similarly, Elijah Price, having been a comic book fan all his life, dedicates his life in finding a ‘’superhero”, one that he doesn’t necessarily idolize, but derives a sense of purpose from. As is shown in the final scene, he literally considers his existence worthy when he “discovers” David and helps him realize his powers, no matter it means, and in the process, brands himself as the brainy supervillain. “I’m not a mistake. It all makes sense”, he states.

In that, while serving as a breakdown of the superhero genre itself, it also becomes a lens to dissect any other modern superhero film that even remotely falls under the same category by virtue of using the same tropes. It is also an increasingly grounded tale: having a superhero capable of flight or of shooting lasers or harnessing thunder would have simply not worked. The film had to be set in the real world, with a hero whose story, and even powers, would have to be increasingly subtle and not too outlandish, the purpose being defeated otherwise; something that even in all its implausibility would make you think that by Mr. Glass’ logic, someone like David Dunn harnessing more or less the same abilities could exist, even if out of sheer fantasy; you are forced to consider a point.

Contrarily, the point could also be that comic book superheroes were in fact inversely based on real life, extraordinary people. Of course, he makes sure that the film is topped off with a horrific, sweeping-the-rug-from-under-you kind of ending, which is his signature by now, truly making this a typical Shyamalan offering.

Relationship With Glass and Split

Well, we all know that Shyamalan would go on to develop an entire trilogy of films based on his tryst with superheroes, beginning with ‘Unbreakable’, followed by ‘Split’ and closed by ‘Glass’. ‘Glass’ also shows the destiny of a number of characters from both ‘Split’ and ‘Unbreakable’, and provides a flawed yet satisfactory conclusion to a story that started close to two decades ago. You can find my detailed take on ‘Glass’, including its plot and ending, here.

With that out of the way, I do not wish to expand on what fates await our favourite characters from all three films, and how the ending of the trilogy meant that superheroes in Shyamalanverse were outed to the world; but rather on how significantly the trilogy is linked, and how even as a trilogy, and not a singular film, the three-part structure may be effectively applied and implied, adding to the overall appreciation of it. Upon closer look, Shyamalan would appear to be experimenting with some sort of fractal theory in film narrative structure, implying that a part of a whole is a whole in itself.

Now, consider this. It is widely known that Shyamalan based the narrative structure of ‘Unbreakable’ on that of a typical comic book origin story, a three part narrative, with the first being introduction to the hero (and villain in most cases). The second one would include either the hero coming to terms with his newfound abilities or the villain putting into place his nefarious plans, sometimes both. The third and final act involves a confrontation, a mano-a-mano between the hero and the villain, wherein the hero emerges victorious. Of course, since this is a Shyamalan film, one could always expect the ending to be non-traditional, but the narrative structure, with a few modifications here and there, remains mostly the same.

However, since all these parts are increasingly grounded given the completely sombre tone of the film, one can easily construe ‘Unbreakable’ to be an origin film. This is also clear since David is only shown fighting crime using his powers on a regular basis in ‘Glass’ first. Drawing a more macro scale of looking at things here, come to think of it, the entire trilogy of films, while each movie in itself individually following a similar structure, is essentially just that: a three-part narrative structure for an origin story of “superheroes” for the world to look at. Considering what happens in the ending of ‘Glass’, ‘Unbreakable’, ‘Split’ and ‘Glass’ can easily be seen as origin, setting up and confrontation. The films can also be seen moving, almost in a rank like fashion, or like an echelon, from the genetic decoding of a hero to a villain, with ‘Split’ proving to be the pit-stop, the in-between, the antihero.

Final Word

I do, in all sincerity, hope that the heaps of praises I have showered upon the film can urge you to watch this 21st Century cult classic if you haven’t already, especially if you are an avid comic book reader and fan like me. Apart from delivering an engaging thriller with a twist that you won’t see coming, it also provides significant commentary on the genre, and given that you keep an open mind about it, I’m sure that you will find most of it relevant; the findings even more so than the commentary. The parallels it draws to comic books, akin to its primary antagonist, Elijah Price aka Mr. Glass, including those deliberately attempted by the director M. Night Shyamalan himself are a definite delight, and the film would come to be known as a celebrated feature in his earlier string of successes.

While Shyamalan seemed to have found his mojo back in ‘Split’, his biggest hit in years, this film might just be the one that we could courageously put in the same bracket as his older films. ‘Unbreakable’, for me, proved to be a psychologically insightful experience. I agree that the film doesn’t give any answers with regards to that, but that doesn’t mean that it doesn’t raise those questions either: what if superheroes were real? What if real people were superheroes? All this and more quietly push ‘Unbreakable’ into the territory of a high concept movie even if on the surface it would look like far from being one. The film’s impact and inferences are gradually and increasingly being recognized by comic book aficionados and film lovers alike.

Read More in Explainers: 47 Meters Down | The Notebook | Fight Club